Paesaggi Informatici

Prefazione di Antonino Saggio

Se è vero che l’architettura si fonda

sui suoi materiali specifici (l’articolazione degli usi, le concezioni

dello spazio, le modalità costruttive e tecnologiche, le ricerche

sul linguaggio espressivo) è altrettanto vero che si costruisce

anche attraverso l'uso di materiali "altri". Materiali apparentemente all’architettura

estranei, ma che in realtà costituiscono la spina dorsale di un

riferimento più ampio e più profondo che lega la riflessione

architettonica al mondo, alla società, alle concezioni scientifiche

e filosofiche del proprio tempo.

Ora il libro Nuovi Scapes che avete tra le mani viene

a completare all’interno di questa collana una sorta di trilogia

caratterizzata proprio dalla presenza al centro della trattazione di un

tema apparentemente eccentrico ma che ha da sempre influenzato la riflessione

dell’architettura: se Alicia Imperiale in Nuove Bidimensionalità

aveva affrontato il tema del substrato informativo e descrittivo

dell’architettura e della sua rappresentazione, e Maria Luisa Palumbo in

Nuovi ventri aveva indagato il rapporto tra uomo (e concezione dell’uomo

e del corpo) e architettura, Paola Gregory si concentra ora sulle

relazioni tra concezione di natura e di paesaggio e l’architettura.

Tutti e tre questi campi sono fecondi sia singolarmente

sia se visti nel loro insieme. E lo sono fecondi, tanto più

perché siamo nel momento di un trapasso. Il suffisso "Nuovi"

che accomuna tutti e tre i titoli, proprio questo sta ad indicare nele

opportunità che si aprono all'architettura all'interno del paradigma

informatico. Guardando insieme i tre volumi si trovano interessanti analogie,

interessanti "movimenti comuni". E’ il movimento verso la complessità,

il movimento verso la profondità concettuale che ci è dischiusa

di fronte.

"I nuovi scapes indicano all’orizzonte un nuovo modo

di vedere, progettare e abitare lo spazio, attraverso l’interpretazione

dell’opera come sistema complesso di connessioni, interscambi e retroazioni,

sempre aperto, flessibile, modificabile." Al contrario di quanto si può

in un primo momento pensare, l’accettazione consapevole del paradigma informatico

e dei suoi strumenti rende più profonde le ragioni, le influenze,

i processi.

All’aprirsi di grandi strumenti di simulazione della

complessità, che è un portato fondamentale della indagine

e della modellazione permessa dalla base matematica scientifica dell’informatica,

si collega un vettore di penetrazione nella ricchezza delle relazioni della

materia, in un continuo ipotizzare relazioni mutevoli e interrelate, in

un porre al centro il metodo delle ipotesi e delle simulazione invece che

gli assunti rigidi della teoria. La ricerca si muove così

in profondità: in una superficie che diventa carica di movimenti

intrecciati e di flussi attivi, in un corpo che e si trasforma sin

nelle sue viscere e appunto in una nuova concezione di paesaggio e di natura.

Ora, il paesaggio quale fondamentale paradigma della

creazione dell’architettura è diventato da almeno un ventennio

parola di riferimento per tutto il dibattito architettonico e Paola Gregory

a questo tema ha già dedicato un bel saggio (La dimensione paesaggistica

dell’architettura, Laterza 1998). L’uomo della civiltà post-industriale

ed elettronica può rifare i conti con la natura perché se

l’industria manifatturiera doveva dominare e sfruttare le risorse naturali,

quella delle informazioni la può valorizzare. Almeno nei paesi tecnologicamente

avanzati, questo strutturale cambio di direzione apre l’opportunità

a un "risarcimento" di portata storica. In zone spesso costruite a densità

altissime si può iniettare ora verde, natura, attrezzature per il

tempo libero. Eppure proprio per le ragioni che dicevamo il processo non

è "di superficie". Non si tratta di circoscrivere e recintare aree

verdi, da contrapporre a quelle residenziali, terziarie, direzionali come

era nella logica dell’organizzare dividendo della città industriale.

Si tratta al contrario di creare nuovi pezzi di città integrate

dove accanto a una forte presenza di natura siano presenti quell’insieme

interagente di attività tipiche della società dell’informazione.

Naturalmente anche gli strumenti cambiano. Se, lo zoning era stato

il modo per pianificare la città industriale attraverso la divisione

in zone tra loro omogenee e distinte che simulava il concetto tayloristico

di produzione industriale, la plurifunzionalità e l’integrazione

è diventata la necessità della città dell’informazione

e delle sue nuove aree anti-zoning. La natura cui questa concezione del

paesaggio guarda non è più quella floreale o liberty e neanche

quella dei maestri dell’organicismo, controcanto al mondo meccanico e industriale.

È diventata appunto una concezione di natura molto più complessa,

molto più difficile, molto più "nascosta" ed è sondata

anche dagli architetti con occhio anti romantico attraverso i formalismi

della scienza contemporanea (i frattali, il dna, gli atomi, i salti di

un universo che si espande, il rapporto tra vita e materia, la geometria

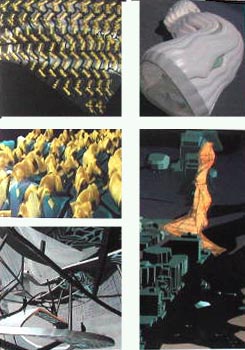

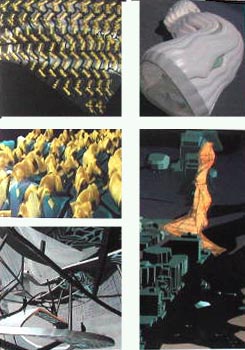

topologica, le forme animate). Insomma, attraverso le categorie della complessità

cui questo libro giustamente dedica spazio. Nascono in questo contesto

le figure dei flussi, dell’onda, dei gorghi, dei crepacci, dei cristalli

liquidi e la fluidità diventa parola chiave. Descrive il costante

mutare delle informazioni e mette l’architettura a confronto con le frontiere

di ricerca più avanzate dalla biologia all’ingegneria alle nuove

fertili aree di sovrapposizione come la morfogenesi, la bioingegneria o

la biotecnologia.

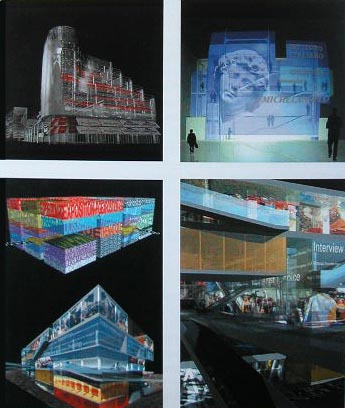

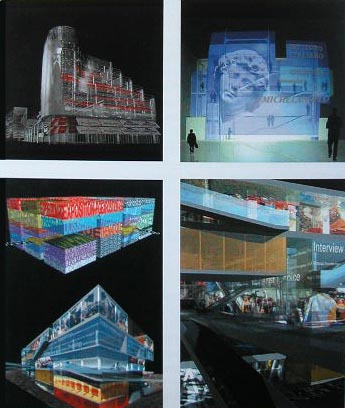

L’idea è che l’architettura dopo essersi fatta

essa stessa paesaggio o nelle stratificazioni e nei palinsesti di Eisenman,

o nel residuale urbanscape di Gehry o nelle onde della Hadid o ancora nei

movimenti scoscesi del compianto Miralles può diventare paesaggio

reattivo, complesso, animato, vivo. L'informatica dunque gioca in questo

contesto quattro caratteristiche chiave:

innanzitutto fornisce i "modelli matematici" per indagare

la complessità chimica, fisica, biologica, geologica della natura

e a partire da questi modelli di simulazione consente di strutturare relazioni

nuove in progetti che ne introitano le ragioni e le dinamiche.

In secondo luogo, l'informatica fornisce armi

decisive per la costruzione reale di progetti concepiti con queste

complesse logiche "all digital" (e finalmente non abbiamo solo parole ma

anche esempi realizzati, basti pensare allo Yokohama Terminal

dei "nati con il computer" Moussavi e Zaera-Polo).

In terzo luogo, l'informatica dota l'architettura

di sistemi reattivi capaci di simulare comportamenti della natura, nella

reazione al clima, ai flussi di uso e ultimamente anche ai comportamenti

emotivi, e offre così una nuova fase di ricerca estetica di cui

ci siamo spesso soffermati parlando delle sfide dell'Interattività.

E in quarto luogo l'informatica, o meglio l'era informatica,

fornisce anche un modello complessivamente diverso di città

e di paesaggio urbano: misto negli usi, sovrapposto nei flussi, aperto

24 ore su 24 con attività produttive ludiche sociali e residenziali

in cui si intrecciano strutturalmente "natura e artificio". Sono Paesaggi

informatici se li guardiamo con occhi aperti al mondo della tecnologia,

New scapes se pensiamo anche all'insieme di riflessioni e tensioni che

questo libro, in un viaggio che non tralascia le implicazioni filosofiche

ma anche le maniere di pensare concretamente ai principi alla base

delle nuove architetture, affronta in un viaggio che, crediamo, appassionerà.

Information Landscapes

Preface by Antonino Saggio

If it is true that architecture is based on its specific

materials (patterns of use, concepts of space, construction methods and

technologies, research into expressive language), then it is just as true

that it is also built through the use of "other" materials; materials apparently

foreign to architecture, but ones that in reality make up the backbone

of a broader and deeper reference connecting architectural considerations

to the world and society, to the scientific and philosophical concepts

of their own time.

The book you hold in your hands, Newscapes, completes

a sort of trilogy in this series, one characterized precisely by the central

presence of a theme that, though apparently eccentric, has always influenced

architectural thought. Alicia Imperiale in New Flatness dealt with the

idea of the informational and descriptive substrata of architecture and

its representation, and Maria Luisa Palumbo in New Wombs investigated the

relationship between man (and the concept of man and body) and architecture,

and now Paola Gregory will concentrate on the relationship between architecture

and concepts of nature and landscape.

All three of these fields are fertile both individually

as well as seen as a whole. They are even more fertile since we are now

at a moment of passage. The prefix "New", that all three titles have in

common, indicates specifically those opportunities that have opened up

for architecture within the IT paradigm. Interesting analogies can be found

by looking at all three volumes together, interesting "common movements".

The movement toward complexity, toward the conceptual depth that has opened

up before us and is revealed in the subtitle Territory of Complexity. "The

new scapes indicate a new way on the horizon of seeing, designing and inhabiting

space through the interpretation of the work as a complex system of connections,

interchanges and retro-actions, constantly open, flexible and modifiable."

Contrary to what one might think at first, the conscious acceptance of

the IT paradigm and its tools makes reasons, influences and processes more

profound.

Along with helping create great tools for simulating

complexity, a fundamental outcome of the research and modeling allowed

by the scientific and mathematical basis of information technology, a vector

is also connected that penetrates into the richness of relations with the

material, in a continuous hypothesizing of changing and interrelated relationships,

in giving center place to the method of hypotheses and simulation instead

of rigid theoretical assumptions. And so research goes deep: into a surface

that becomes loaded with interwoven movements and active flows, into a

body that is transformed to its core, and even into a new concept of landscape

and nature.

Landscape as a fundamental paradigm in the creation

of architecture has, for at least twenty years or so, been a reference

word for the entire architectural debate. Paola Gregory has already dedicated

a book to this theme (La dimensione paesaggistica dell’architettura, [The

Landscape Dimension of Architecture] Laterza, Bari 1998). Human beings

from the electronic and post-industrial civilization can re-settle their

account with nature because if the manufacturing industry dominated and

exploited natural resources, then the information technology industry can

help increase their appreciation and conservation. At least in technologically

advanced countries, this structural change of direction opens up the opportunity

for a "compensation" of historic proportions. Green areas, nature, structures

for leisure time activities can all now be placed in areas built up frequently

with very high density construction. In other words, precisely because

of those reasons we have already mentioned, the process is not "on the

surface". We are not dealing with circumscribing and fencing off green

areas to contrast with those other residential, tertiary and managerial

areas as was part of the logic of organizing by dividing the industrial

city. On the contrary, we mean creating new integrated parts of the city

where that interacting group of activities typical of the information society

exist alongside a powerful presence of nature. Naturally, the tools change

as well. If zoning was the method for planning the industrial city through

the division into homogeneous zones that were distinct among themselves

and simulated the Tayloristic concept of industrial production, then multi-functionality

and integration have now become the necessities for the information city

and its new anti-zoning areas. The nature intended in this concept of landscape

is no longer floral or "liberty-style"; neither is it the nature of the

masters of organicism, counterpoint to the mechanical and industrial world.

This concept of nature has in fact become much more complex, much more

difficult, much more "hidden" and is also investigated by architects with

an anti-romantic eye through the formalisms of contemporary science (fractals,

DNA, atoms, the leaps of an expanding universe, the relationship between

life and matter, topological geometry, animated forms). In other words,

through the categories of complexity to which this book rightly dedicates

space. Hidden in this context are the figures of flows, the wave, whirlpools,

crevasses and liquid crystals; fluidity becomes the key word. It describes

the constant mutation of information and places architecture face to face

with the most advanced research frontiers, from biology to engineering,

to the new fertile areas of superimposition such as morphogenisis, bioengineering

or biotechnology.

The idea is that architecture, after having made itself

into landscape, whether in the stratifications and palimpsests of Eisenman,

or the residual urbanscape of Gehry, or the waves of Hadid or again in

the precipitous movements of the late Miralles, can become a reactive landscape,

complex, animated and alive. Thus Information Technology plays three key

roles in this context:

First of all, it supplies the "mathematical models"

to investigate the geological, biological, physical and chemical complexity

of nature and, beginning with these models of simulation, allows the structuring

of new relations in projects that exploit reasons and dynamics.

In the second place, IT supplies decisive weapons for

the real construction of projects conceived with this complex "all digital"

logic, (and finally we not only have words but real examples as well, just

consider the Yokohama Terminal by those two architects "Born with the Computer",

Moussavi and Zaera-Polo);

In the third place, IT endows architecture with reactive

systems capable of simulating types of behavior in nature, in reacting

to climate, usage flows and ultimately also emotional behavior, and so

offers a new phase of esthetic research we have frequently discussed when

speaking of the challenges of Interactivity.

And in the fourth place, IT, or rather the Information

Age, also supplies an overall different model of the city and urban landscape:

mixed in its uses, superimposed in its flows, open 24 hours a day, with

"nature and artifice" structurally interwoven into production, leisure,

social and residential activities. These are Information Landscapes if

we look at them with eyes open to the world of technology, New Scapes if

we also consider the group of considerations and comparisons that this

book confronts in a voyage that neglects neither philosophical implications

nor the methods of concretely considering the basic principals of this

new architecture, and one that we feel is very exciting.